There hasn't been a lot of action on this blog site so far this school year—but not because there aren't things worth writing home about! As you can imagine, I (Mr. Meadth) have been much busier on the ground each day with cleaning and supervision, let alone teaching the engineering class.

But some things are worth documenting and celebrating. So let's jump in!

1. Four New Freshmen

We took four new engineering students into the freshman class. A big welcome to Hunter, Abby, Teleios, and Eliana. These junior engineers are hitting the ground running, despite all the challenges. They are learning trigonometry before their time, taking baby steps into the world of computer-aided design (CAD), and just generally being awesome. Welcome, freshmen!

|

| Hunter, Teleios, and Abby (Eliana couldn't make this photo, but she's just as much a part of this group!) |

2. College-Level Statics... From a Textbook

Despite my propensity to always design my own curriculum from the ground up, I tried something new this year: a textbook! It turns out this was the perfect year in which to do this, as it matched well to the statics studies that we've always done anyway. Don't be led astray by the name—Statics for Dummies—the lighthearted tone helps high schoolers get through those pesky equations. For those engineering parents out there, you'll find all of the fun you can handle in vector calculations, force couples, and free-body diagrams.

3. Independent Mode

This is a grand experiment, and one that we committed to from the start of the year. Can we commit to a full year of engineering studies in independent mode? Some would say that it's never been tried, but this is the year to come up with new solutions! Despite the absence of stimulating classroom discussions, this has allowed students to take seven classes plus engineering, and it allows students to watch at their own pace. Students have watched 18 videos so far this year, and responded with written assignments and discussion boards. They are now eagerly discussing their community design project in a shared Google Doc, which brings us to Number 4...

|

| Acceleration sums in three dimension, anyone? |

4. Community Design Project

I'm so happy with how this project is rolling forward! We have two "clients", Mrs. Christa Jones on the San Roque campus and Mr. Gil Addison at PathPoint, who works with residents in wheelchairs. Our student teams are busily designing an adjustable standing desk for Mrs. Jones and an adjustable computer desk for Mr. Addison. Both of these designs are required to involve electrical/mechanical aspects, such as motorized lifts or built-in LED lighting. Once the student teams finalize their designs, complete with drawings and CAD models, I (Mr. Meadth) will be building their designs myself—in the interest of staying as contact-less as possible.

5. Lots of Publicity

6. Major Grant Win

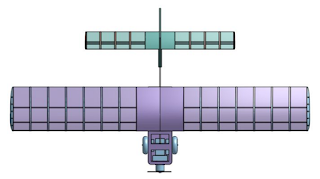

Is it just me that believes in our outstanding Providence engineering program? Is it just the university lecturers who receive our already-highly-trained students? Am I just blowing my own horn over here? Apparently not! The Toshiba America Foundation decided that our second-semester robotics project was something worth funding, and we are pleased to announce that over $4,000 of the very latest in classroom robotics equipment will soon be arriving on campus. This will be put to use in our Mars Rover project, where different student teams will design, build, and code different components of one big vehicle. I'm looking forward to this one. Thanks, Toshiba!

|

| One of the advanced Vex V5 sets: coming soon! |

As always, stay posted for more exciting announcements. Our junior engineers are doing something very different, but making the most of it. I'm confident that their skills and experience will remain at the very highest level amongst similar programs in our area. Keep it up, students!

--Mr. Meadth